TARGET 150415

Choquequirao,

Lost City in the Clouds

The first rays of morning sunlight illuminate

the great stone altar, streaming through

a square opening over my head. "Inti camac

sumac," chants the priest. Soaked in sweat,

I fight the bindings holding me to the

stone as the grinning, looming, scarlet-cloaked

figure slowly brings down a gleaming,

bloodstained bronze knife toward my heaving chest.

"Jefe, buenos dias - cafe?"

Startled suddenly awake, I thankfully greet a

smiling Pancho, our camp cook, handing a cup

of wake-up coffee through the tent door. Whew -

I make a silent oath to myself to avoid the

second round of piscos that we had passed around

the campfire last night.

We are on our way back to the mysterious and

magnificent mountain Inca city in the remote

cloud-forested Andes of Peru that has been the

focus of my research and explorations for many

years and numerous expeditions.

I am traveling with an interesting group of

ethno-botanists. Our objective is to identify

plants and trees that may have been introduced

by the Inca residents and may still live on in

the tangled vegetation surrounding the recently

cleared stone walls and buildings.

There is always something more to learn at the

Inca's second Machu Picchu.

The Inca royal estate and ceremonial complex,

Choquequirao is perched majestically at

9,800 feet of elevation on the cloud-forested

ridge of a glaciated 17,700 foot peak.

The traditionally sacred Apurimac River,

reportedly the longest headwater source of the

Amazon, roars through a deep canyon some

5000 feet below. The site lies 61 miles west

of Cusco in the rugged, remote Vilcabamba

range of the Peruvian Andes, far distant from

roads, trains and the tourist hordes that mob

Choquequirao's famous sister estate, Machu Picchu.

Choquequirao remains one of the great, rewarding

travel destinations of the Americas that still

retain some of the excitement and discovery

experience of the past.

It is a truly 'lost city,' abandoned sometime

around 1572 when the holdout last Inca ruler,

Tupac Amaru was captured in the distant

jungles, dragged back to Cusco and executed

by Spanish colonial authorities. The ancient

houses, temples, canals and walls were soon

reclaimed by the silent, green, primeval

forest only to be rediscovered and revealed

in recent times. Located on the far, unpopulated

and geographically hostile side of the immense

Apurimac Canyon, the region remained disconnected

from the farms, villages and roads of developing

Peru.

It is little known that Yale professor Hiram

Bingham, the now famous scientific discoverer

of Machu Picchu in 1911 was inspired to launch

his return to Peru and archaeological explorations

after a visit to Choquequirao in 1909. Bingham

visited Choquequirao twice, the second time with

a crew of surveyors, cartographers and specialists

to produce the first map and scientific description.

During the early 1990s, the Peruvian government

took interest, beginning a careful archaeological

and restoration project that continues today. In

1995, a new trail and foot bridge crossing the

Apurimac was completed, giving more access to

adventurous travelers and pack-horse-supported

small tour groups, contributing to the income

and employment of enterprising local families.

The previous year I had arrived for the first time

with a filming expedition, reopening the long,

multi-day trail across the rugged highlands from

Machu Picchu with picks, shovels and machetes.

Now twenty years later, I am returning yet again

to contemplate Choquequirao's mysteries and matchless

beauty, trekking in by the shorter, two-day route

from the road head near the community of Cachora.

University of Colorado archeoastronomer, Kim Malville

and I recently published my life's work in the

Andes and our studies together of Choquequirao,

in a new book entitled "Machu Picchu's Sacred

Sisters, Choquequirao and Llactapata." The book

focuses on similarities with Machu Picchu,

concluding that Choquequirao was modeled and

geocosmically located after its older ceremonial

sister.

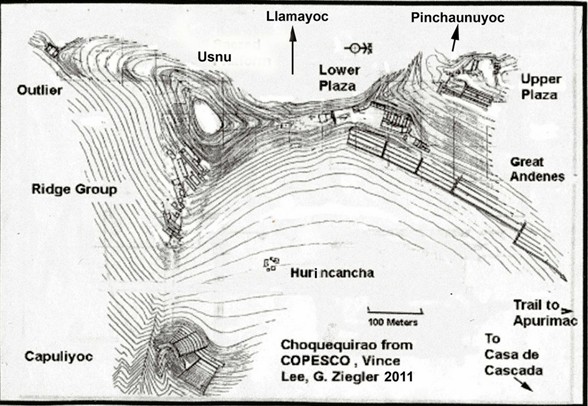

We describe our collective findings and contributions

of colleagues in detail with a few adventures thrown

in from journals as well. The chapters cover main

and outlying groups, architectural features,

construction techniques, probable usage, function,

and how the Inca design incorporates Andean

astronomy and the sacred landscape. In brief,

we suggest that Choquequirao was designed and

constructed during the reign of the Inca, Topa

Yupanki, sometime in the late fifteenth century,

modeled after his father, Pachachuti's estate,

Machu Picchu.

Topa Inca had Choquequirao built as his own Machu Picchu.

Experience from field investigations indicates Inca

monumental sites were carefully planned and designed

according to astronomical alignments, precisely

placed in relationship to sacred rivers, mountains,

and celestial phenomena.

Choquequirao fits this view. It was uniquely

located at a convergence of sacred terrain

features with celestial events most important to

the Inca state religion and Andean tradition

in particular, the June and December solstices.

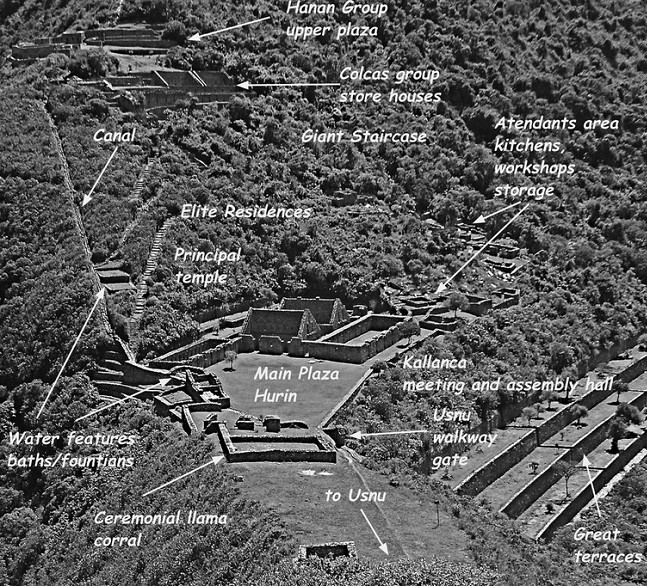

Like Machu Picchu, important, high-status construction

is centered on a ridge top with a higher mountain

behind and a lower distinctive promontory in front,

with a sacred river flowing below in view. Each

hosts a series of fountains or baths passing through

ridge top groups.

During the height of the Inca empire, 1450-1526,

both Choquequirao and Machu Picchu would likely

have served as a provincial administrative center.

There is reasonable evidence that Machu Picchu

and Choquequirao may have also provided a

seasonal pilgrimage destination for

regional state-sponsored ceremonial events.

It is easy to envision a great procession of corn

beer, chicha drinking pilgrims singing and chanting,

conch shells blowing, melodic flutes forlornly

playing, drums reverberating from the canyon walls

as the outer gate is approached. Pots and cups are

ritually broken and offerings, borne in for the

mountain spirits, apus, are piled about as the

ceremony starts, carefully choreographed by richly

dressed attendant priests.

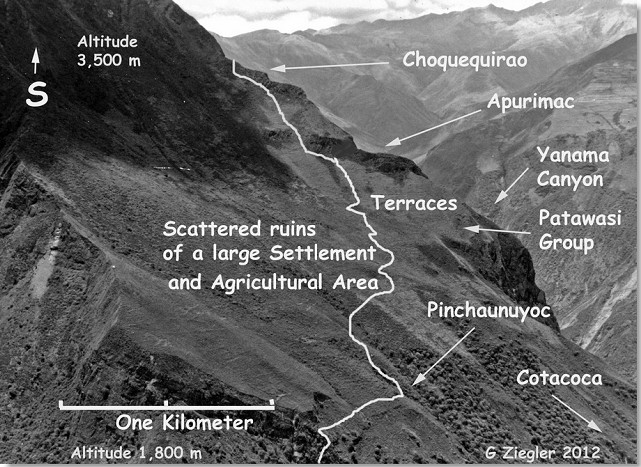

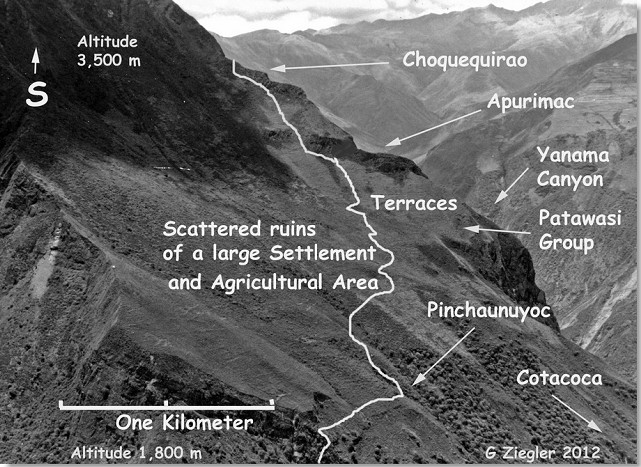

Evidence that coca was widely grown, coca store

houses, llama pens and a unique llama train mural,

support Choquequirao as an important coca growing

and distribution center. Intensive cultivation,

ongoing construction and maintenance would have

required a large resident population. Remains of

a large settlement of simple, round, wood

dwellings contained by low stone walls is situated

over an area of several square miles, above an

outlying temple water shrine, Pinchaunuyoc. These

would have housed the needed workers well away

from privileged resident Inca administrators,

attendants, and main group temples.

Visiting Choquequirao

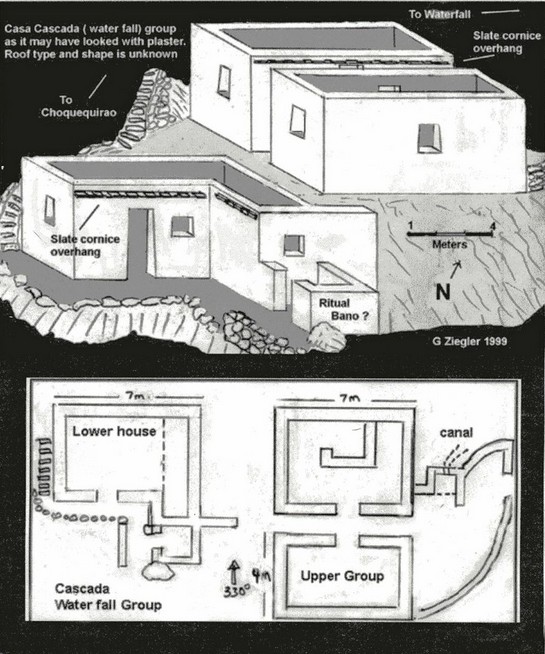

Upon arrival at Choquequirao, one should allow several

days to explore the site and visit the two most

important outlying groups. Pinchaunuyoc, several

miles away, requires several thousand feet of climbing

down and back up for a round trip. The waterfall group,

Casa de Cascada, uses up the better part of a day

to visit and return.

Both are well worth the time.

One of the rewards of visiting Choquequirao is that

it has remained well off the beaten path. Only a few

hundred visit during the dry season as compared to

more than two thousand daily at Machu Picchu.

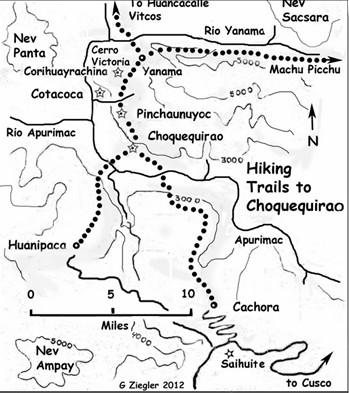

Arriving by the shortest route requires two days

of strenuous hiking.

Descending into the deep Apurimac then back up some

4,500 feet to reach the site is like crossing

Arizona's Grand Canyon.

One either carries a heavy backpack or hires

local packers to bring the needed supplies with

horses or mules. The best solution is to sign on

with one of the Cusco-based trekking agencies

that regularly take small groups of two to six

there during the dry season months of April into

December.

It is possible to ride a horse most of the way

but good horses are hard to come by. Most of

the local packer stock is not up to standards

of safety and dependability nor well cared for.

Some trekking agencies are marginal. A good test

is the cost. If it seems really cheap, there is

a reason. Carefully research and checking

references before signing on is recommended.

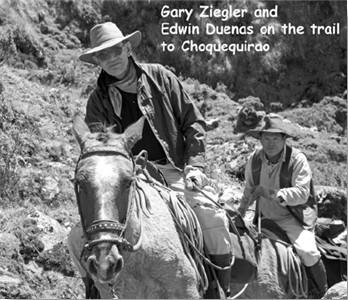

An old Cusco friend and Inca expert, Edwin Duenas,

operates trips by horseback and foot with

customized itineraries to Choquequirao and

other sites for individuals and small groups

out of Cusco. Edwin has worked with me as a field

research associate for many years. We have led

groups together on a number of occasions. I highly

recommend contracting him as the best archaeological

guide and outfitter available.

www.adventurespecialists.org

The small community of Cachora sits in a lush,

broad valley leading down to an immensely steep

drop to the Apurimac River. Agriculture and

travel in the valley goes back to pre-Inca times.

To CachoraThe present colonial-period community

was established as a part of Hernando Pizarro's

holdings or encomienda in the the mid-1500s. Life

here was pretty much unchanged until the Maoist

terrorist group, Sendero Luminoso, took violent

control in the 1980s.

Many villagers with training or education were

rounded up and executed as a preliminary to

establishing absolute control.

I heard these horror stories when visiting there

just after government troops and national police

evicted the Senderistas following the capture

of Sendero leader Abimael Guzman in 1992. Work

at Choquequirao and growing tourism has put

the community back on track.

Traveling from Cusco, allow the better part of

a day to arrive at Cachora. As of this writing,

it takes five to six hours. The highway access

regularly slides away with slow, repair-created

detours and hosts increasingly heavy truck

traffic. Some of the route has returned to pot

holes and extreme dust. No solution has appeared

to solve these delays. Highways can't be built

to hold on steep, unstable, Andean mountain slopes.

Of course, the Inca knew this and carefully placed

their foot and pack llama-travelled roads up,

down and around where modern roads won't work.

The Cachora road turns off of the mostly-paved

Central highway just past the Inca monument,

Saihuite, to wind down several thousand feet to

the community. There are a few small, rustic places

to stay at with basic Andean food: chicken,

soups and beer.

Although serious trekkers can reach the camp at

Choquequirao in one horrendous, long day, two

days is the reasonable norm. A minimum of six

days should be allowed for a visit and round

trip from Cachora. The usually well-maintained

trail follows along the rim of the Apurimac canyon,

with considerable up and downs before finally

dropping steeply to the river and bridge. There

are two suitable places to camp. The first is high

up before the drop to the river. Someone has built

a couple of shelters there, cold showers and piped

in water. There are ample, flat places for tents.

Usually someone is there to sell beer or Inca Kola.

The second camp is at the river. The government

agency, COPESCO, built a structure for housing

workers while building the bridge. As of this

writing it has been renovated and is serviceable.

There are plenty of tent sites and one can cool

off in the river. It is hot at an altitude of

around 5000 feet.

The vegetation looks like Sonoran Desert, cactus

and thorny acacia trees. Small biting gnats lurk

in ambush so bring repellant, long sleeves and a

closable tent. The trail switch-backs steeply up

after the bridge, climbing steadily until arriving

at Choquequirao.

Several small farms, chacras, are passed along the

way and higher up are small clusters of houses,

fields and corrals. A campsite with water and a

latrine has been built about an hour or so from

the archaeological complex, where one can camp

for a small fee.

Just before reaching the edge of the designated

zone, the government INC, now renamed the Ministry

of Culture, (MC), has placed a small toll booth

where a fee is collected. As of our last visit,

it was forty Soles which is probably justified by

the new camping site with flush toilets and a cold

water shower house. From the camp, it is easy to

follow the pathways around the main groups which

are marked by signs.

Carry Machu Picchu's Sacred Sisters with you to

help identify the groups, structures and alignments

of the various buildings, walls and features. Visiting

the distant groups of Capullyoc, Hurincancha or the

Casa de Cascada may require a guide. Allow most of

a day for any of these. Llamayoc, the llama mural

in stone, can be seen in an hour or two as it is

close down from the Lower Plaza.

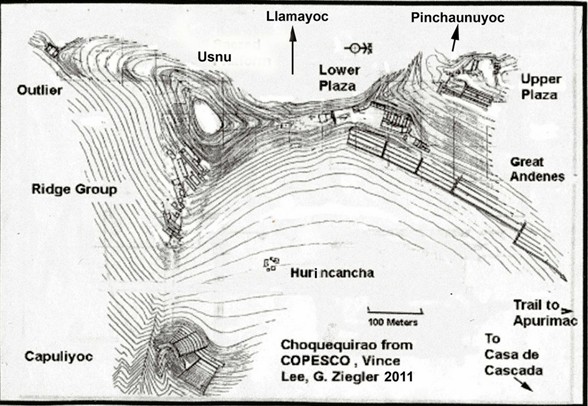

A walking tour of Topa Inca's estate: suggestions

that may be helpful.

1) From the developed camping area follow a

small path leaving from the shower house uphill

to the main trail above. Turn left on the trail,

following it southward. Within a few minutes,

you are on the large, walled terraces. The trail

continues until you reach the far end. It then

turns right and upward a short distance to enter

the main (Hurin) plaza. The plaza can be the

central staging point for visiting all of the

main groups.

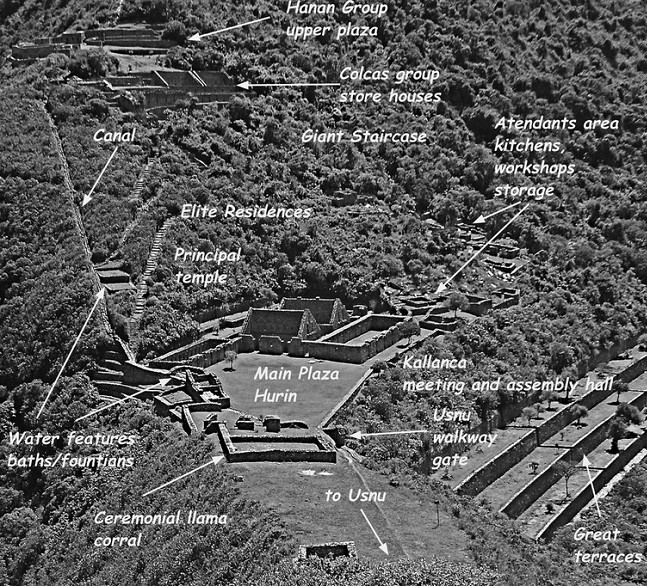

2) Using the annotated photo diagram in the

book, visit and examine the building groups

and water features that surround the plaza.

3) Next, find a trail leaving from the northwest

corner of the plaza climbing upward or north to

the upper plaza group. There should be a sign

in place. In any case, carry a compass to aid

navigation and to observe alignments of the

features as we described in the book.

4) Climb upward following the trail near the

restored water canal several hundred feet to

reach the upper, Hanan plaza and the collection

of interesting buildings, fountain structures

and temples that face a spectacular view of

the deep Apurimac Canyon below.

5) Returning to the main plaza below, follow a

different trail bearing off to the left or

east side of the upper plaza, down through a

group of large buildings that we identify as

store houses, colcas. Find the December

solstice-aligned, Giant Staircase just below

the colcas. The trail continues down, passing

by a group of crude structures that we believe

were attendant and kitchen quarters, to again

enter the main plaza.

6) From the main plaza, pass through the big

double-jamb doorway on the left or east end

of the curious multi-angle, Hurin temple forming

the southern end of the plaza. Passing several

low-walled structures, which probably were holding

pens for llama related rituals, the path climbs

several hundred feet up to reach the big flat

topped hill we call the Usnu. Spend time here

to admire the overwhelmingly powerful view of

the surrounding Andes as did the Inca residents.

This is a great place for photos when the

never-certain Andean weather permits.

7) Continue over the Usnu hill southward

following a path down the descending ridge

crest. After passing several small platforms

and walls, the trail ends at what Bingham named

the "Outlier Group" now called the Casa de

Sacerdotes (House of the Priests).

The view down the big canyon and surrounding

ice peaks is, of course, awesome.

8) Returning back up the ridge, take a small

trail branching off to the right or east just

a bit above the Casa de Sacerdotes. This route

leads through dense, cloud forest tangle around

to an east-facing ridge running down from the Usnu

hill which hosts the Ridge Group (Pika Wasi). From

the uppermost group structures, find a good trail

leading uphill back to the main plaza.

9) From the plaza, a sign marks an entranceway

at the water feature group that is the start of

a steeply descending trail to the Llama mural

terraces (Llamayoc) some distance below (west).

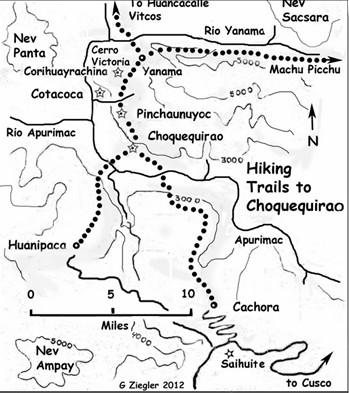

Trails mapAllow ample time for this visit. It is

a demanding climb back to the plaza.

This itinerary will require the better part of a

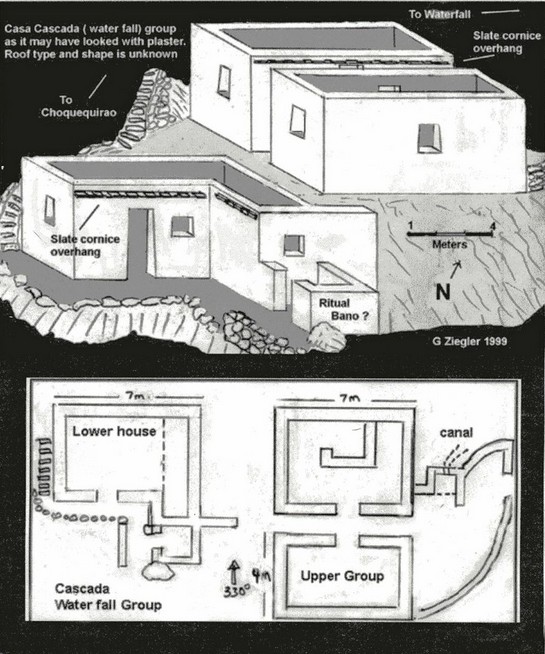

day. A full additional day should be set aside to

visit Pinchaunuyoc or the Casa de Cascada. The

Hurincanca group has been reclaimed by dense

vegetation so is sadly again lost. Finding and

studying the site will require a good day and a

crew with machetes. We do have the GPS location.

Our 1999 diagram is in the book available for

a future visit and study.

The Casa de Cascada is located some 1500 feet

down-slope below the camping site. The trail is

good but the start is not well indicated. If

possible, ask one of the visiting group tour

guides who may know, or one of the site workers

if you speak a bit of Spanish. A trip to the

hanging terraces, Capuliyoc, further along the

same trail should be included on the same day.

The other satellite group associated directly

with Choquequirao, Pinchaunuyoc is well worth

a visit but is a few miles distant, involving a

drop of several thousand feet on a very steep

switchbacking trail. It is a favorite overnight

stop on the long route to and from Machu Picchu.

It should be done as an overnight trip from

Choquequirao. Again, best to ask directions

as suggested above.

Heading for Cusco - on the road again.

A reality of trail travel in the steep Andes is

that slides and floods frequently remove sections

of trails. During May of 2011, a tremendous rock

slide briefly blocked the Apurimac which backed

up to destroy the bridge on the Choquequirao route

from Cachora. It was just reopened in August

of 2014.

Anyway, the flora study completed, we are

homeward bound. The day breaks bright and clear,

despejado as we say in the equatorial Andes.

After a brilliant Andean sunrise, our sunrise

photographers return and camp is packed. All mount

the rested, energized horses to trot cheerfully

along good, near-level, trail traversing high above

the roaring Apurimac River below. Later today, we

must descend to the river and cross on

a swaying cable-suspended box. Some seem to

greet this expectation with limited enthusiasm.

Today's journey is comparable to a crossing of

the Grand Canyon but by now all are fit, and

comfortable with long descents and slow, steady

climbs. We ride what we can but like me, some

walked much of the way, particularly on steep

difficult trail. Anyway, it is good to have a

trusty, calm mount to hop on to when the need

moves you. More, we carry no burdensome day packs

or gear, which is stashed in the saddle bags

traveling nearby when needed.

I travel light, wearing running shoes with legs

protected for riding by leather gaiters called

in the riding trade, half chaps. These serve well

for hiking through brush and snake country as well.

Several hours' travel downhill places us at the

trail's end, bridge abutments with forlornly

sagging cables and alas, no flooring. The bridge

is gone. An immense rock slide had dammed up the

Apurimac just downriver, creating a dam that backed

up water to the bridge, destroying planking and

lower supports.

Choquequirao was effectively closed except for

hardy travelers coming and going by the long

arduous route in and out via Yanama or by the

swinging cable car. This reflects a millennium

of hard life in the Andes. It has never been easy

and the natural environment is cruel to the

careless or unfortunate. Civilizations have

come and gone here, even for the privileged.

We are happy to just cross the river on whatever

means available. That means is an oroya, a long

cable and a small box like contraption attached

on pulleys with a pull rope to haul one across

above the raging rapids. Our trusted horses and

pack stock are necessarily left behind. New mounts,

sturdy mules and saddle horses await us on the far

bank if we successfully survive the cable crossing,

which I can happily report we do.

We face bonding with a new wrangler crew and

unknown new equines but, this is the stuff of

adventure. All rise admirably to the occasion.

We are soon sharing tales in a comfortable camp

some distance up from the buggy river bottom on

an ancient, pre-Inca, breezy plateau with running

water and bottled beer, recently developed as a

tourist encampment. They even have a flush toilet

marginally in operation although several of us opt

for the nearby woods. In any case, the local

mosquitoes relish the opportunity for exposed bottoms.

Enough time in the wilds - "the bright lights of

Cusco are shining like

diamonds, like ten thousand

jewels in the sky."

The next morning, we mount up or strike out

walking. It is a mere four thousand feet uphill

and ten miles to our awaiting transport near

the village of Cachora. We get it done without

mishap. Evening finds us enjoying a late meal

in Cusco's favorite pub, noted British ornithologist

Barry Walker's Cross Keys. It was a great,

successful adventure…

Maybe I will have that second Pisco?

Gary Ziegler is a field archaeologist with a

geology background, a mountaineer and explorer

who has spent a lifetime finding and studying

remote sites in the Vilcabamba range of Peru's

southern Andes. He is a Fellow of the Royal

Geographical Society and of the Explorers Club.

He has featured in documentary films for the

BBC, Discovery Channel, Science and History

Channels. His work has been published in

numerous professional journals, and he is

co-author of "Machu Picchu's Sacred Sisters:

Choquequirao and Llactapata." He has taught

at Colorado College and Peru's national

university, San Marcos. He was awarded the

title "Distinguished Lecturer" at NASA's

Marshal Space Center in 2013. His home base

is the 4000-acre Bear Basin Ranch in the Sangre

de Cristo mountains of southern Colorado.

He can be contacted at:

info@adventurespecialists.org

and www.adventurespecialists.org

Photo credits: Thanks to Steve Bein,

Ken Greenwood,

Paolo Greer, Lillian Roberts

and Hugh Thomson.

FEEDBACK MAP

If you got impressions for

which this feedback is

insufficient, more information,

pictures and videos can

be found at the following web sites:

Facebook

Wikipedia

Trekking to Choquequirao, Peru’s remote Inca ruins

Many thanks to Ray McClure for creating this target.